Our friends Gary, (one of my former high school/prep school classmates), and his wife, Belinda, had been roaming about on an extended road trip and we were the final stop on their agenda… Given the fact that history and historic sites are a major point of interest for them, I planned a few appropriately focused days for us.

I took this photo of Gary and Belinda on our deck. Of course, we weren’t on the road to historic sites all the time that they were here. We spent lots of down time at our house, sharing stories and learning about each other’s life styles. Life is a lot different in East Tennessee than it is in the high desert near Tucson Arizona!

I kept the first day simple and close to home. We started out at the Fort Loudoun State Historic Park. This park covers 1,200 acres and it is the site of one of the earliest British fortifications on what was, in 1756, the western frontier. Not only does the visitor’s center provide information and a chance to visit the Fort’s gift and book shop, it also offers lots of information on the area’s history. FYI…although donations are appreciated, admission to the Visitor’s Center and the Fort itself is free!

The Fort Loudoun Visitor’s Center is really a mini museum that serves to provide a bit of background for the fort and what life was like for those that lived here. The visitor’s experience starts with a 15 minute introductory film but then one can tour the exhibits of artifacts recovered from the site as well as period pieces from that era.

In the

photo above, one can spot the famous or infamous ‘red coat’ uniform worn by the

British during the time the fort was in existence. Among other items, the display case to the

left contains a “Brown Bess”, the standard issue .75 caliber musket used during

this era. Accurate to only about 100

yards at the most, the “Brown Bess” was supported by light cannons and “wall

guns”, both shown in the photo.

Basically, a wall gun was just a beefed up musket that had up to a 1

inch, 25.4 caliber bore and filled the gap between the cannons and the standard

firearm.

I included this photo showing a model of the fort just to give some overview of the fort itself…something that is hard to capture with a camera unless its drone mounted. The area encompassed by the fort is really quite large.

What

caused the fort to be built in the first place?

During the French and Indian War (1754 – 1763) the British Colony of

South Carolina felt threatened by French activities in the Mississippi

Valley. So, to counter the threat, the

Colony sent the Independent Company of South Carolina to build and man what

became Fort Loudoun.

Why all the concern? Well, like almost everything else now and then, it came down to commerce and trade. The addition of the fort helped to ally the Overhill Cherokee Nation with South Carolina and guarantee that trade would continue as normal between the Cherokee and South Carolina.

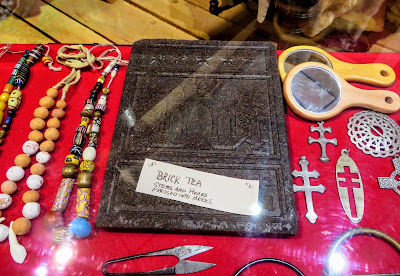

British

traders provided European goods to the Cherokee. These items included kettles, textiles,

scissors, knives, guns, ammunition, metal hatchets, hoes, brick tea (see

above), beads and other trinkets while the Native Americans provided deerskins,

beeswax and river cane baskets.

After leaving the Vistor’s Center, the path wanders through some trees before it emerges near the fort’s ‘sally-forth’ or “sally port” on the land side portion of the fort. There were several huge trees along the way…some perhaps as old as the fort itself. I couldn’t resist my photo op! I love anything that makes me look small!

FYI, a

‘sally port’ or ‘sally forth’ is any small defensible opening in a fort’s

perimeter through which troops or other personnel regularly enter and exit the

fortification.

This is a broad view of one section of Fort Loudoun. The fort and its close by areas of historical significance occupies about 50 acres in the Park itself. There is a block house located just across Tellico Lake from the fort. This British stronghold, on what was then the frontier of the colonies, was named after the Earl of Loudoun, who was the commander of British forces in North America at the time. Keep in mind that back in the late 1750s, this strategic fort overlooked the Little Tennessee River...and the lake didn't exist.

Visiting

Fort Loudoun during “Garrison weekends” is the best way to visualize life at

the Fort during the French and Indian War.

There are daily demonstrations of artillery and musketry, the infirmary,

blacksmithing, wood working, laundry, leather working and other trades. Garrison weekends are also free…the exception

being the 18th Century Trade Faire.

However, during our visit, we were on our own as we checked out the barracks, shops, storehouses and other structures at Fort Loudoun. Around the outside there are examples of defensive ditches, hedgerows, movable wooden spiked fences or “Cheveaux-de-Frise”…and even a guard house near the main gate.

Feelings

between the garrison at Fort Loudoun and the local Cherokee were friendly at

first but in 1758 hostilities arose between the Anglo-American settlers and the

Native Americans. After the massacre of

several Cherokee chiefs who were being held hostage at another fort, the

Cherokee laid siege to Fort Loudon in March of 1760. Although the garrison held out for several

months, dwindling supplies forced them to surrender in August of the same

year. Hostile Cherokees attacked the

withdrawing garrison during its return to South Carolina…killing more than 2

dozen and taking most of the survivors as prisoners. Many of these captives were ransomed… When

the fort was next revisited by British troops, it had been destroyed.

Laurie and I have visited the fort when reenactors were spending the weekend living life as it had been back in the late 1750s. Crowded into the cabins, with wool uniforms on the men, the ladies dressed in multi-layered clothes, insects, heat, etc., we could only imagine what the fort’s inhabitants experienced when the fort was active defending the frontier. Those bunks look cozy don’t they!? Imagine the bedbugs, lice and other nasties…

Mother

Nature reclaimed the site and there wasn’t any public recognition of the fort

until 1917. Late that year the Colonial

Dames of America placed a market at the site of the fort. In 1933, the Tennessee General Assembly

purchased the land and created the Fort Loudoun Association to manage it. After archeological excavations were

completed by the Works Progress Administration, the fort was

reconstructed. It was designated as a

National Historic Landmark in 1965…and when Tellico Lake was created in 1979,

the fort was once again reconstructed, this time high above the water levels of

the new lake/dam impoundment.

To learn

more about historic Fort Loudoun and the state park, just go to https://fortloudoun.com/.

The Sequoyah Birthplace Museum is located just across the road from the Fort Loudoun State Historic Park. In this case, the museum is a property of the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indians. The goal of this museum is to promote the understanding and appreciation of the history of the Cherokee people. This museum was built in 1986 on the shores of Tellico Lake but it had been several years since we’d visited and it had been totally renovated with a new exhibit being installed in 2018.

The featured

exhibit is entitled “The Story of Sequoyah”.

He was born ca. 1776 at the village of Tuskeegee, a village which was

located near where the museum is today. Sequoyah’s

father was a Virginia fur trader and his mother, Wut-the, was the daughter of a

Cherokee Chief.

Sequoyah was born into changing times. European traders and settlers were moving into the land causing conflict and interrupting the Cherokee’s way of life. He adapted to the changes, marrying another Cherokee and becoming a silversmith by trade. Sequoyah and many other Cherokees even enlisted on the side of the United States and fought under General Andrew Jackson to fight British troops and their Creek Indian allies in the War of 1812.

He’d been

exposed to the concept of writing early in his life, but Sequoyah never learned

the English alphabet. However, he’d

observed that white soldiers could write letters to their families, read

military orders and record observed events while the Cherokee could not… When

the war was over, his thoughts about Cherokee literacy blossomed into a

full-blown effort to create a writing system for his people.

Sequoyah’s

quest was a single-minded focus on solving the mystery of the “talking leaves”

(alphabetic letters). He spent years

almost alone, facing social derision, tribal suspicion, enduring a family

rebellion…but he was determined to create a written language for the Cherokee

After

many efforts…and almost as many failures…Sequoyah reduced the thousands of

Cherokee thoughts to an alphabet consisting of 85 symbols which represented

different sounds.

Sequoyah’s next quest was to convince the Cherokee leaders that his new language was actually functional…and that it could help the tribe more positively communicate and deal with changing times. He started out by making a game of the new writing system and teaching it to his daughter Ayoka. After 12 years of trials and tribulation, Sequoyah used Ayoka to help demonstrate the language to tribal leaders and that changed their attitudes! They bought into his alphabet and their new written Cherokee language.

Although Sequoyah didn’t have a formal education, he combined his Cherokee heritage, his skills as a silver artisan and his hopes for the Cherokee people…and translated the sounds of the Cherokee spoken language into symbols that his people could easily understand and learn. In just a few months after Sequoyah and Ayoka introduced the written language to tribal leaders, the Cherokee began using his syllabary to change themselves into a literate society.

The

Cherokee syllabary was introduced to the Cherokee Nation is 1821. By 1825, much of the Bible and many hymns had

been translated into Cherokee. By 1828,

they were publishing the “Cherokee Phoenix”, the first national bi-lingual

newspaper, along with numerous religious pamphlets, educational materials and

legal documents. Within 5 years, the

Cherokee literacy rate surpassed that of surrounding European-American

settlers.

It was

quite an accomplishment! In the history

of the world, no one other than Sequoyah, who himself wasn’t literate in any

language, perfected a system for reading and writing an existing spoken language. To recognize his accomplishments, the

Cherokee Nation awarded a silver metal to him that was created in this honor,

as well as a lifetime literary pension.

He served his people as a statesman and diplomat until his death in

1843.

It is

said that Sequoyah’s work has had international influence, encouraging the

development of at least 21 syllabaries impacting perhaps as many as 65

languages in North America, Africa and Asia.

To learn

more about Sequoyah you can just go to: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sequoyah. For more information about the Sequoyah

Birthplace Museum here in Eastern Tennessee, go to http://www.sequoyahmuseum.org/.

That’s

about it for now. We will continue with

our historical adventures with Gary and Belinda in my next post!

Just

click on any of the photos to enlarge them…

Thanks

for stopping by for a visit!

Take

Care, Big Daddy Dave