…continuing with our tour of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum which is located in St. Michaels Maryland. We were nearing the end of our family trip to explore part of the Delmarva Peninsula.

This

final post about our visit to the Museum will look at a variety of exhibits…in

no particular order.

The first photo shows a punt that's equipped with a punt gun… These were tools used in the commercial waterfowl hunting trade. Restaurants in the big cities not only craved oysters by the bushel, but also a steady supply of waterfowl for their clientele. The Chesapeake Bay area is a critical and massive stopover for migrating ducks, geese, etc.

Punts are

small flat-bottomed boats with a square bow.

They are used in smaller rivers and in shallow bodies of water. They’re propelled by pushing with a pole on

the river bed. Punt guns are oversized

smoothbore percussion guns that are far too big to fire from the shoulder so

they’re mounted at the front of the punt and could be aimed by the

shooter. Guns like this were charged

with huge amounts of gun powder and shot…and then were aimed at a flock of

water birds. When fired, a hundred or

more ducks could be harvested, just from one shot.

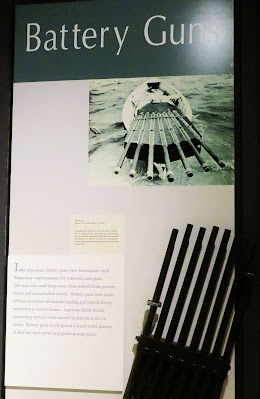

The second

photo is one of the results of punt guns being outlawed. To work around their inability to employ punt

guns, market hunters built ‘battery guns’.

Basically they consisted of 3 – 12 old muzzle loaders secured to a

wooden frame. A powder filled ‘trench’

connected to vents caused the barrels to fire in a series. With the spread of

gun barrels, they covered a wider area with shot pellets. However they were dangerous to operate…

In any

case, the use of punt guns or battery guns severely depleted the number of wild

waterfowl and by the 1860s most states had banned the practice. The Lacey Act of 1900 banned the transport of

wild game across state lines. Then a

series of Federal laws in 1918 outlawed market hunting altogether.

The

Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum has an impressive collection of artifacts

related to water fowl hunting as a pastime and occupation. As shown above this collection includes

firearms and gunning skiffs but in addition there is a sizable collection of

decoys…backed up by sinkboxes, tools and clothing.

The

Museum’s large decoy collection includes working goose, duck, swan, and

shorebird decoys made by more than 70 regional makers…many of them rather

famous for their skills. This display is

part of the Museum’s long term exhibition “Stories from the Shoreline”.

Note: Not being a hunter I had to look up the

term ‘sinkbox’. It is a hunting blind

consisting of a weighted, partially submerged enclosure that can hold one or

more hunters. Sinkboxes are suspended

from a floating platform and are placed in calm water so the hunter can wait

for his opportunity with the waterline roughly at shoulder height. Since the early 1900s, sinkboxes have been

illegal in the USA

The first photo shows the “model shop” at the Museum. The volunteer Maritime Model Guild supports the Museum’s curatorial needs with exhibition models and building kits that are available at the Museum Store. The Guild also offers classes for building models from scratch. The Model Guild also hosts radio-controlled skipjack sailing races. The Museum’s extensive ship model collection numbers more than 300 vessels.

I suspect

that this handsome and detailed model of the “Peggy Stewart” was made by a

member of the Model Guild. The original “Peggy

Stewart” was a Maryland cargo vessel that, with its cargo of tea, was burned in

Annapolis Maryland on October 19, 1774. It’s

destruction was as a punishment for attempting to get around the boycott on tea

imports that had been imposed in retaliation for the British occupation of

Boston following that city’s “Tea Party”.

The burning of the “Peggy Stewart” in known as the “Annapolis Tea Party”.

Note: Incidentally, the most important cargo

aboard the “Peggy Stewart” was removed from the ship before she was

burned. That cargo consisted of 53 ‘indentured’

servants.

The first photo shows the tugboat “El Toro” after it had been acquired by the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad and it had been renamed “Chessie”…and later “W.J. Harahan”. The “El Toro” was built in 1928 and spent many years of her life moving railroad car barges across Chesapeake Bay.

The

second photo shows the 12 foot high compound 2-cylinder steam engine the tug

boat was equipped with. This engine

produced 700 horsepower…just a fraction of the power needed for today’s

tugboats. As I’d mentioned, the Museum

covers a wide variety of Chesapeake Bay endeavors…

…and the

variety of displays at the Museum continues.

In this case it includes a collection of about 1500 historic and

contemporary paintings, prints and other artwork. Works by regional artists as well as

contemporary artists are featured along with posters, print advertisements and

detailed drawings.

I failed

to note the photographic artist who took this eye-catching aerial photo of a

creek or small river where it emptied into part of Chesapeake Bay. Nevertheless, I’d love to have the original

of this photo on my wall at home! Nature's designs are endless...

I do love

ship paintings…and this one is no exception.

This is a painting depicting the pungy “Geneva A. Kirwan” sailing along

the Bay. This vessel was built in

Madison Maryland in 1882. The painting

was completed in 1933 by Louis Feuchter.

Feuchter was born in 1885 and died in 1957. He was known for his maritime paintings and

he was quite prolific.

Many of

Feuchter’s paintings can be purchased for less than $1,000 with many in the

$500 range. The highest price for one of

his paintings was for a painting of the “Pungy Amanda F. Lewis”, which sold for

$4,312.

Note: Yes…I did have to look up the ship style

referred to as a ‘pungy’. Basically, a

pungy is a two-masted schooner that was used for oyster dredging in Chesapeake

Bay.

The “Stories from the Shoreline” exhibit also addresses the mass production and marketing of motorboats. This modest display of outboard motors caught my eye as I’m always looking for items that tie back to my former ‘work life’ in some way.

In this

case, that small outboard motor to the left center of the photo did tie back to

a former employer. The close-up photo of

the top of that little 7.5 HP “Sea King” outboard motor shows that it was

manufactured for and sold by Montgomery Ward.

The company sold Sea King outboard motors from 1933 until 1986. (I didn’t

join the company until 1987)

Primary

manufacturers of a variety of Sea King outboard motors included Gale, Clinton

and Chrysler Marine. Some discontinued Lockwood

(Evinrude/Outboard Motors Corporation) motors were also relabeled Sea

King. The same thing happened with some

Thor outboards. Apparently old/antique Sea

King outboard motors are quite collectable with a number of them for sale

on-line. Another company advertises that

they have replacement parts available.

This

rather worn vessel is a five-log Tilghman Canoe. It is the last of the 68 built by Robert

Lambdin of St. Michaels Maryland. These

canoes were used in the fisheries industry along the bay. This one was built in 1893 and it cost

$212.57 at the time. In 1910 this ‘canoe’

was converted to a powerboat by removing the centerboard and adding a propeller

shaft. It had been abandoned along the

shore of Chesapeake Bay for several years before it was rescued and stabilized

for the Museum.

…continuing

with my boating or boat theme. This is

the “Bessie Lee”, a 20 foot long Seaside Bateau that is located in the Small

Boat Shed at the Museum. This is a

two-sail periauger rig or “cat-yawl”. In

broad terms, a periauger or peroque is a shallow draft, often flat-bottomed

2-masted sailing vessel which also carried oars for rowing. These vessels were often created by digging

out a log, splitting it longitudinally and then adding at least one keel plank

between the halves.

Only

small vessels with a shallow draft could enter many of the inlets around the

bay. But these bateaus were used by

local merchants as well as blockade runners during the Revolutionary War. A family’s boat ca. 1850s may have looked

like this. Bateaus did come in varying

sizes depending on their planned use.

This is a

Smith Island Power Crabbing Skiff. Smith

Island watermen used similar boats to sail to their crabbing grounds where they

caught soft crabs using a dip net.

Originally these were sailing skiffs but engine-powered boats like this

began being used ca. 1907. Sailing

skiffs continued to be used in the commercial crab fishery until WWII.

After

retirement from the fishery business, this skiff was used for pleasure. She was found stored in a Pennsylvania barn

but she has been restored to her original configuration and paint colors. She was built ca 1925.

This

early cabin cruiser was built in 1926 by the Mathews Company in Port Clinton

Ohio. The original owner spotted it on

display at the Maryland Yacht Club in Baltimore and he paid $6,500 for it…a lot

of money back in 1926. Named the “Isabel”,

she was a ‘show boat’ so it came equipped with anchors, life rings, monogrammed

china, linen and silver. Some of those

artifacts are also on display at the museum.

The

family of the original owner spent almost 70 summers cruising the Chesapeake

Bay on “Isabel”. Her heirs were among

the founders of the Classic Yacht Club of America and they participated in

numerous rendezvous, parades and cruises.

With the exception of a new diesel engine, the boat retains most of its original

equipment and fittings. In 1995 the family

donated this classic 38 foot cruiser to the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum

I’ll end our tour of the Museum with a photo of a more traditional Chesapeake Bay boat. The 51 foot long “Old Point” was built in 1909. The builder used 7 pine logs pinned together and then hewn to shape to construct this vessel. She is a good example of the fleet of boats operating out of Hampton Virginia from the 1910s through the 1960s that were designed to dredge crabs during the winter.

From

December through March, captains and crews lived on their boats so they could

leave every morning and dredge for crabs all day. In the summer and fall, “Old Point” would

carry fish and oysters to packing houses or to market. The former owner of “Old Point”, Captain

Ernest Bradshaw, had to transition throughout the year…from fish, to oysters

and to crabs. Part of the Museum’s ‘floating

fleet’, “Old Point” was donated to the Museum by Mr. and Mrs. Richard C. DuPont

back in 1984.

And so

ends our tour of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum. To learn more about the museum, its exhibits,

waterborne tours, hours of operation and entry fees, just go to Chesapeake

Bay Maritime Museum | Home Page (cbmm.org). We certainly enjoyed our experience at the

Museum!

Just

click on any of the photos to enlarge them…

Thanks

for stopping by for a visit!

Es un genial museo. Te mando un beso.

ReplyDelete